Remote learning among immigrants

Post by Lindsay Criqui. Colgate Class of 2022.

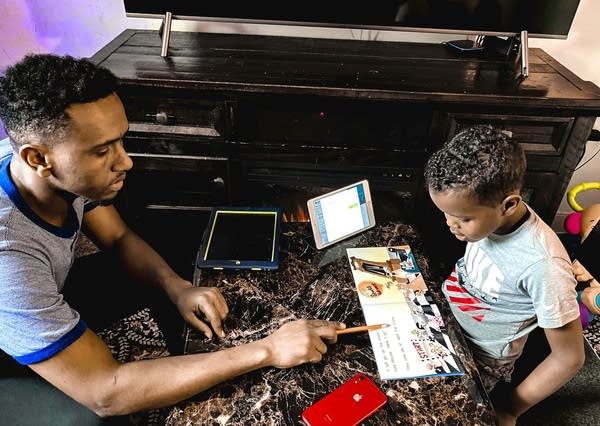

The impact of COVID-19 on the entire world is immeasurable, as all aspects of daily life have been altered due to the pandemic. One aspect of everyday life that has been dramatically changed is the approach to learning and education across the world. Immigrant and English learners (EL) students have faced many problems that come with remote learning. Their learning process has been greatly interrupted, as they benefit greatly from in person instruction. From the lack of access to technology and internet service to not receiving the same amount of help and assistance, many immigrant children and EL students have fallen behind in their education.[1] The uncertainty as to how much longer remote instruction will last has also created concern to how to get immigrant students back on track in their education. As schools plan to reopen, there is worry about funding and the ability to dedicate the already limited funding to help the EL and immigrant students catch up on their education.

Since the start of remote instruction, many immigrants and EL students have fallen off from their education and turned away from their studies. For example, in California, some high school students have distanced themselves from learning and turned to working in the fields. A counselor in Monterey county, California explains that “The longer [students] are disengaged from it the harder it is to ask them to go back, we have to be more enticing than the money they are going to make.”[2] In order to get the EL students back on track, EL students should have priority to return to school when schools return to in person instruction. EL and immigrant students should have priority over other students as they benefit the most from in person interaction and learning in a classroom. Furthermore, there should be increased resources in schools to address the schooling that was lost by EL and help them catch up in their education. It is estimated that due to state and local budget cuts, there will be a lack of funding for schools and that states will need to turn to the government in order to help out these EL students. When deciding where these funds should go, EL instructors should also be involved in the planning and be able to help make decisions. These instructors will have more insight on how to properly dedicate funds in order to help EL and immigrant students.

As immigrant students and EL students transition to online learning, their language barrier presents another obstacle. Many EL students live in a household that might not speak English. This makes it harder for EL students to get their work done.[3] Immigrant parents have struggled helping their children, as they might not be familiar with English based learning. Furthermore, as there has been a transition to remote learning, there is inequality in access to technology and internet connection. There is around 35% of low-income households across the United States that do not have a reliable internet connection. In addition, low income households also have a problem with accessing a computer at home. One in four teens in low income households do not have access to a computer. Out of these lower income households, Hispanic teens are the most likely to not have access to a computer.[4]

In class we discussed that there is higher return to education in the destination country for immigrants due to the language benefits and higher quality of education in the destination country. In other words, taking a class in the destination country’s language will be more beneficial as the immigrant is able to better adapt to the language and also obtain education. The textbook explains that Hispanic teens lower the United States immigrant high school enrollment rate, as they have the lowest percentage of students enrolled.[5] As a result of this pandemic, there has been a trend that immigrant students will have less incentive to attend their remote learning and all together might fall behind or drop out of their learning, depending on their age.[6] As they drop out of their remote learning, it is possible there will be a higher amount of immigrant and EL students who join the labor force and search for work rather than continue their education.

[1] Sugarman, Julie, and Melissa Lazarín. “Educating English Learners during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Policy Ideas for States and School Districts.” Migrationpolicy.org, 1 Oct. 2020, www.migrationpolicy.org/research/english-learners-covid-19-pandemic-policy-ideas.

[2] Aguilera, Elizabeth. “Migrant Students Work in Fields during COVID School Closures.” CalMatters, 26 June 2020, calmatters.org/children-and-youth/2020/06/california-teens-school-closures-migrant-farmworkers-fields-coronavirus/.

[3] Yang, Hannah. “Immigrant Families Face Challenges with Remote Learning.” MPR News, MPR News, www.mprnews.org/story/2020/04/13/immigrant-families-face-complex-challenges-with-minnesotas-distance-learning.

[4] Auxier, Brooke, and Monica Anderson. “As Schools Close Due to the Coronavirus, Some U.S. Students Face a Digital ‘Homework Gap’.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 27 July 2020, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/16/as-schools-close-due-to-the-coronavirus-some-u-s-students-face-a-digital-homework-gap/?utm_content=buffer09ef5.

[5] Bansak, Cynthia, et al. The Economics of Immigration. Routledge, 2020.

[6] Sugarman, Julie, and Melissa Lazarín, 1 Oct. 2020